In Brief

Helping children who struggle with anger can be both challenging and deeply rewarding. Many arrive in therapy after their emotions have boiled over—incidents at school that risk suspension or expulsion, frequent clashes at home that strain family bonds, or conflicts with peers that make friendships hard to sustain.

Every angry outburst signals a child trying to communicate something they can't yet put into words. Anger is a normal feeling and a typical part of childhood development, often showing up as tantrums or defiance as kids learn to navigate their world. However, when anger becomes frequent, intense, and disrupts daily life and relationships, it calls for therapeutic intervention.

Early intervention is key to helping children develop healthy coping strategies before anger patterns become deeply ingrained and harder to change. This guide offers therapists strategies for assessment, intervention, and working with caregivers to help children express their emotions in healthier ways and develop useful emotional regulation skills.

Root Causes and Patterns

Emotional dysregulation in children rarely stands alone. The anger we see often comes from underlying conditions like trauma, ADHD, anxiety disorders, stress, neurodivergence, or living in complex family dynamics. Recognizing these connections allows us to address root causes rather than just managing surface behaviors.

Children with trauma histories may feel anger as a protective response to perceived threats. Their nervous systems stay hypervigilant, interpreting neutral situations as dangerous. Similarly, children with ADHD often struggle with impulse control and emotional regulation, leading to explosive reactions when frustrated or overwhelmed.

Anxiety can appear as irritability and anger, particularly in children who lack the words to express their worries. Neurodivergent children, including those on the autism spectrum, may experience sensory overload or communication challenges that lead to angry outbursts. Family dynamics like inconsistent parenting, high conflict, or stress can intensify these problems.

Clinical presentations often include explosive outbursts that seem disproportionate to triggers. These children may show persistent irritability, defiance toward authority figures, and tantrums that last beyond what is developmentally expected. In some cases, physical aggression, verbal outbursts, and property destruction may occur during these outbursts.

Assessment & Diagnosis—When is Anger a Concern?

During intake, distinguishing between typical developmental anger and clinical concerns requires careful attention to three key factors: duration, intensity, and frequency. Typically, anger in children tends to be brief, proportionate to the trigger, and resolves within minutes. When anger persists for hours, appears disproportionate to situations, and occurs multiple times per week, therapists may start to consider the presence of an underlying emotional or behavioral disorder

Screening for these conditions plays a significant role in assessment. Consider these common presentations:

- Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD): Look for severe, recurrent temper outbursts occurring three or more times weekly for at least 12 months, with persistent irritability between episodes.

- Attention/Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD): Assess for impulsivity, emotional dysregulation, and frustration intolerance that accompanies attention difficulties. The NICHQ Vanderbilt Assessment is a useful tool for measuring these symptoms.

- Trauma History: Screen for exposure to adverse childhood experiences, noting hypervigilance, emotional numbing, or explosive reactions to perceived threats.

- Learning Disabilities: Evaluate whether academic frustration contributes to behavioral outbursts, particularly during homework or school-related activities.

Gathering insights from various contexts improves diagnostic accuracy. Request input from teachers about classroom behavior, peer interactions, and academic triggers. Caregivers can complete standardized measures like the DSM-5 Level 2 Anger Parent Form, which uses a 5-point scale to assess anger severity over the past week. For children aged 11-17, the DSM-5 Level 2 Anger, Child (DSM-5 II Ang-C) self-report measures provides valuable perspective on internal experiences of anger.

When assessing anger outbursts, document specific examples across settings. Questions to consider asking include:

- Does the child explode only at home or also at school?

- How long do the outbursts typically last, and what does recovery look like afterward?

- Are there identifiable triggers (e.g., transitions, perceived unfairness, limit‑setting)?

- How intense are the outbursts—verbal aggression, property destruction, physical aggression?

- What strategies have caregivers or teachers already tried, and how effective were they?

- Are there warning signs before the anger escalates (e.g., physical cues, withdrawal, pacing)?

- How does the child describe their anger—do they feel it builds gradually, or “comes out of nowhere”?

- Is the child able to reflect on the incident afterward, or do they minimize/deny the behavior?

- Are the outbursts causing significant impairment (e.g., suspensions, strained friendships, family conflict)?

- Is there a pattern tied to time of day, fatigue, hunger, or overstimulation?

Understanding these patterns helps differentiate situational stressors from pervasive emotional regulation difficulties that may need targeted intervention.

Therapeutic Strategies & Child-Centered Interventions

Effective anger management with children goes beyond reducing outbursts—it’s about equipping them with tools to understand and regulate their emotions in developmentally appropriate ways. Interventions work best when they are child‑centered, engaging kids through language, activities, and strategies they can relate to.

Anger journaling is particularly beneficial for children who can write or draw. Encourage kids to track their anger triggers, physical sensations, and thoughts using simple prompts like "What happened when…?" and "How did my body feel?" For younger children, picture-based emotion charts or drawing their feelings can serve the same purpose.

Cognitive restructuring helps children identify and challenge unhelpful thoughts that fuel anger. Teaching kids to recognize "hot thoughts" like "It's not fair!" or "Everyone hates me!" and replace them with cooler alternatives builds emotional flexibility. Use age-appropriate language: "Is that thought helpful or hurtful?" works better than complex cognitive terminology.

Emotion labeling exercises expand children's emotional vocabulary beyond "mad." Practice identifying subtle differences between frustrated, disappointed, annoyed, and furious. Games like "emotion charades" or using feeling thermometers make this skill-building engaging.

Mindfulness-based tools provide in-the-moment regulation strategies:

- Deep breathing techniques: Teach "birthday candle breathing" (inhale deeply, blow out slowly) or "five-finger breathing" where children trace their hand while inhaling (tracing a finger up) and exhaling (tracing the finger down)

- Counting strategies: Count backwards from 20, count red objects in the room, or use multiplication tables for older children

- Calm corners: Create designated spaces with sensory tools, not as punishment but as self-regulation zones

When shame or self-criticism accompanies anger, introduce self-compassion practices. Help children develop kind self-talk: "Everyone makes mistakes" or "I'm learning to handle big feelings." Drawing from compassion-focused approaches, normalize anger as a protective emotion while teaching gentler ways to meet underlying needs.

Parent & Family Strategies: Supporting the Child System

Parents act as the primary examples for emotional regulation, making their involvement vital for successful anger management interventions. Parent Management Training (PMT) offers structured approaches that change family dynamics through proven techniques.

Core PMT strategies include:

- Positive reinforcement: Notice when children behave well and offer specific praise for calm behavior and attempts at managing emotions

- Strategic ignoring: Disregard minor attention-seeking misbehaviors while maintaining safety boundaries

- Consistent consequences: Provide predictable, calm responses to inappropriate behaviors without reacting emotionally

- Clear limit-setting: Define and communicate expectations before situations occur, not during emotional moments

Modeling emotional regulation requires deliberate practice. When you feel frustrated, explain your coping process: "I'm feeling angry right now, so I'm going to take three deep breaths." This kind of self-talk shows that everyone experiences anger and demonstrates healthy management strategies in action.

Create physical spaces that aid regulation. A "calm corner" differs from a time-out—it's a shared space where children choose to practice self-soothing with sensory tools, books, or calming activities. Parents can visit this space with their child during calm moments to reinforce its positive associations.

Coordinating with schools ensures consistency across environments. Share successful strategies with teachers and request regular updates about triggers and progress. Evidence-based parent coaching protocols offer structured frameworks for developing these skills systematically, providing step-by-step guidance for implementing behavioral strategies while maintaining warm, supportive relationships. Regular practice sessions help parents internalize these approaches until they become natural reactions during challenging moments.

Cultural Considerations

Anger expression in children cannot be fully understood outside the cultural context in which they are raised. Cultural values, family expectations, and community norms all influence how children learn to identify, express, and regulate strong emotions. For therapists, attending to these factors is essential to avoid misinterpreting behavior, over‑pathologizing normal differences, or overlooking underlying needs.

Norms of Emotional Expression:

Some cultures encourage children to be more expressive and assertive, while others value restraint and deference. A child who raises their voice at home may be viewed as disrespectful in one family system but seen as a normal assertion of autonomy in another. Therapists should explore family beliefs about what is considered appropriate anger expression and how caregivers respond when a child becomes upset.

Parenting Practices and Expectations:

Disciplinary approaches vary widely across cultures. While some families emphasize open dialogue and emotional validation, others prioritize obedience, respect for authority, and strict behavioral control. These expectations shape how anger outbursts are perceived and managed. Asking parents how they were taught to handle anger growing up can provide valuable context for understanding their current responses to their child.

Language and Emotional Vocabulary:

Not all families have a shared language for discussing emotions. Some may lack culturally familiar words for feelings like frustration or disappointment, leading children to act out physically rather than express emotions verbally. Therapists may need to provide alternative tools—such as visual aids, stories, or metaphors—that align with the family’s cultural framework.

Community and Social Factors:

Cultural context extends beyond the home. Community norms, school expectations, and peer interactions all affect how anger is understood and expressed. For example, children from marginalized groups may face stereotypes that frame their anger as aggression, increasing the risk of school discipline or involvement with juvenile justice systems. Therapists should remain alert to the role of systemic bias and advocate when needed.

By incorporating cultural considerations into assessment and intervention, therapists can create a more accurate, supportive, and effective framework for helping children manage anger.

Practical Tools, Resources & Developmental Activities

Child-friendly tools turn abstract emotional concepts into experiences children can understand and practice. Worksheets with emotion monsters let kids draw or color their anger, giving it a shape and size outside themselves. Stories about characters managing big feelings make the experience relatable while teaching coping strategies through narrative.

Effective tools for different age groups include:

- Emotion diaries: Simple templates with faces, colors, or weather symbols help children track daily feelings

- Anger thermometers: Visual scales showing anger intensity from "calm" to "exploding" teach emotional awareness

- Body mapping exercises: Children color where they feel anger in their bodies, building mind-body connection

- Coping cards: Portable reminders of calming strategies kids can keep in pockets or backpacks

Games make skill-building fun. "Anger charades" lets children act out what anger looks, feels, and sounds like in a playful context. Board games with emotional regulation challenges provide practice during calm moments.

Developmentally tailored interventions ensure support matches the child’s age. Programs for younger children (ages 4-7) use puppets, songs, and simple activities to introduce emotional concepts. These approaches focus on basic feeling identification and simple coping tools like breathing exercises disguised as fun activities.

For older children and adolescents (ages 8-16), interventions include more complex cognitive strategies, peer discussion, and real-world problem-solving scenarios. These programs address the social challenges of managing anger in school settings, friendships, and family relationships while developing resilience skills that go beyond anger management.

Monitoring Progress & Outcome Evaluation

Keeping track of progress in anger management involves systematic documentation that captures both measurable changes and improvements in behavior. Behavioral charts and anger diaries serve as key tools, allowing you to follow the frequency, intensity, and duration of outbursts over time. These visual aids help children recognize their own progress while providing concrete data for planning treatment.

Key tracking methods include:

- Daily behavior logs: Record specific incidents, triggers, and coping strategies used, noting successful attempts to de-escalate situations.

- Weekly rating scales: Use standardized measures like the Affective Reactivity Index (ARI) to track levels of irritability and compare scores across sessions.

- Multi-informant reports: Collect monthly updates from teachers and parents about changes in classroom behavior, interactions with peers, and home dynamics.

- Relationship quality indicators: Observe improvements in sibling relationships, friendships, and parent-child bonding through structured interviews.

Progress involves more than just reducing symptoms. Look for signs of increased emotional awareness, such as children identifying their triggers independently or expressing feelings before they escalate. Resilience indicators include recovering more quickly from setbacks, trying to repair conflicts, and showing empathy toward others' emotions.

Parent and teacher stress levels often decrease as children's anger management skills improve. Check in briefly to gauge their confidence in handling outbursts and their own emotional well-being. When caregivers report feeling less overwhelmed and more equipped with strategies, it indicates positive changes in the family system.

Adjust the intensity of treatment based on progress. If improvements level off, consider adding family sessions or exploring underlying issues. When children consistently demonstrate new skills in different settings, gradually space out sessions while maintaining periodic check-ins to ensure progress continues.

Key Takeaways

Helping kids manage anger effectively involves a thorough approach that looks at emotional growth, family interactions, and any underlying issues. The best strategies mix skill-building with broad support, recognizing that children's anger doesn't usually occur on its own.

Core components of effective treatment include:

- Developing emotional literacy: Teaching kids to recognize, name, and express their feelings before they escalate into behavioral outbursts

- Using proven interventions: Applying established methods like CBT techniques, mindfulness practices, and structured behavioral plans suited to their developmental stages

- Involving the whole system: Encouraging parents, teachers, and other caregivers to actively participate in the treatment process

- Focusing on skill-building: Going beyond just reducing symptoms to develop long-term emotional regulation abilities

A combined treatment approach leads to the best outcomes. Therapy sessions focused on the child offer direct instruction through age-appropriate activities and cognitive strategies. At the same time, educating caregivers ensures consistent application of behavioral plans across different environments. This dual approach fosters lasting changes in both the child's ability to manage emotions and the family's response.

Practical implementation tips:

- Use standardized assessment tools like the ARI or DSM-5 Level 2 Anger scales for initial measurement and tracking progress

- Keep a collection of interventions ready for various age groups

- Schedule regular sessions with caregivers to support strategies at home

- Consider evaluating for comorbid conditions when anger appears with ADHD, trauma, or learning difficulties

- Record specific improvements in behavior and relationship quality, not just reduction in symptoms

Remember, anger often points to unmet needs or underlying issues. Addressing these root causes while building coping skills leads to lasting improvements in children's emotional well-being.

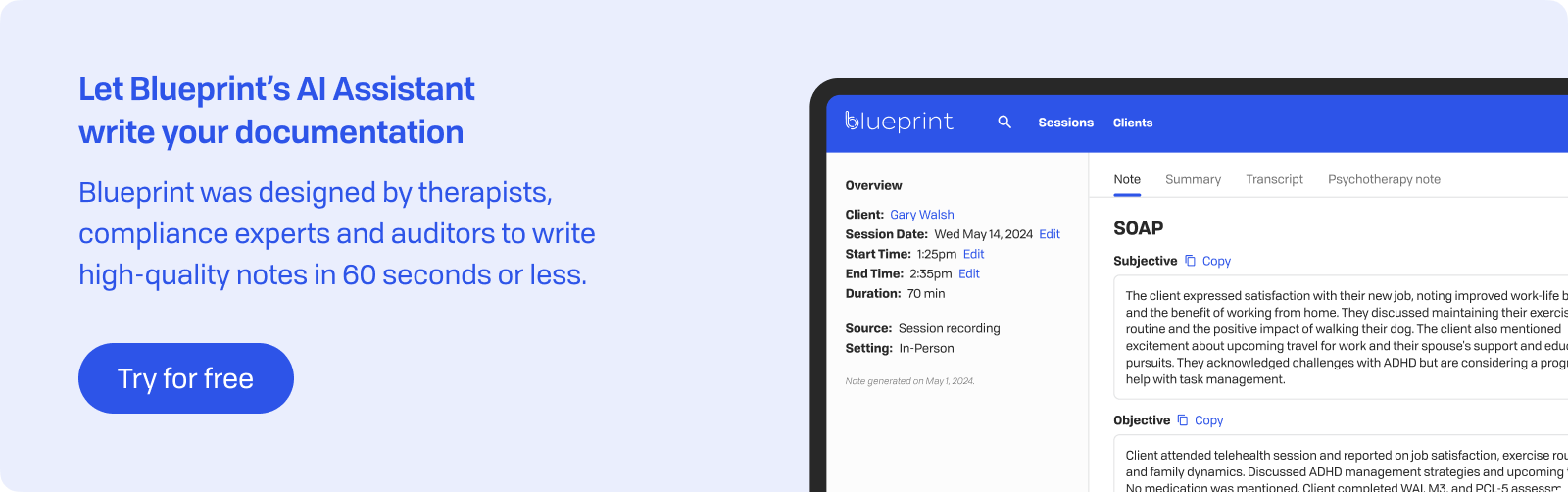

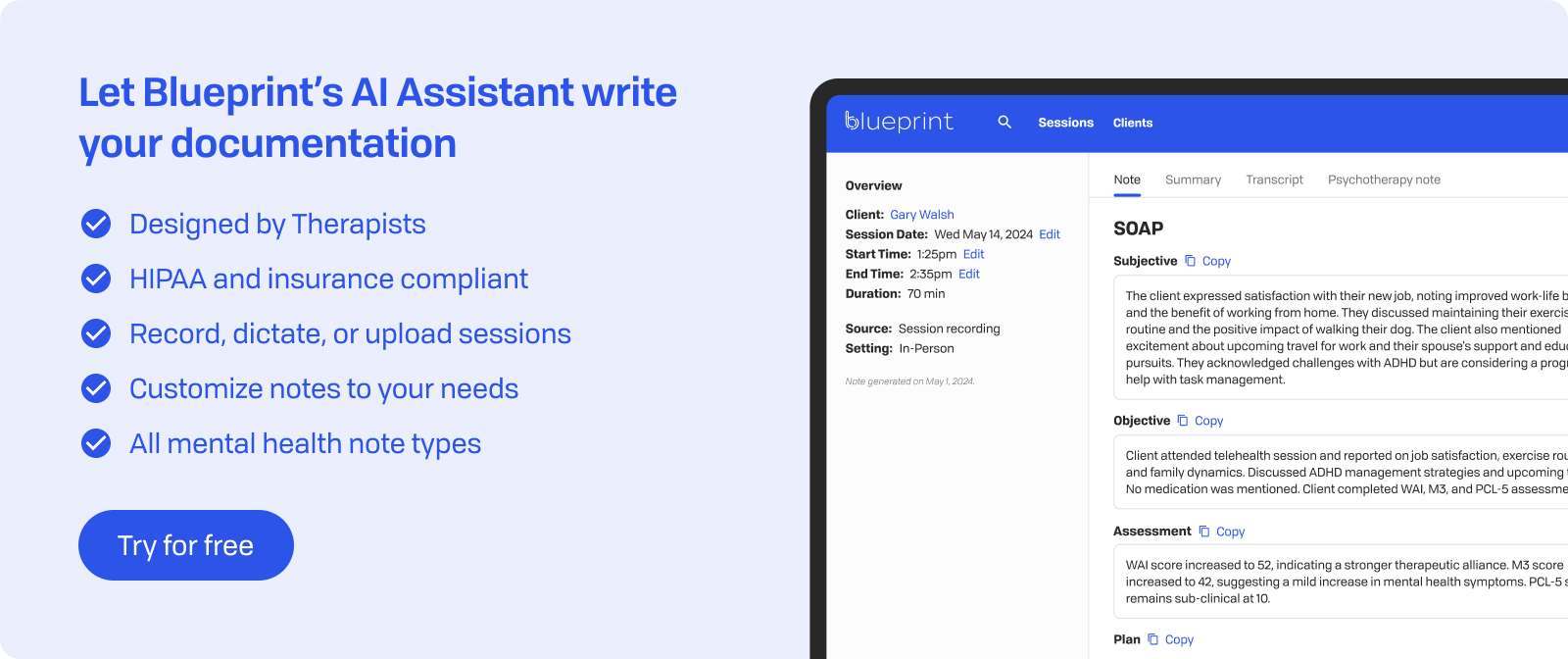

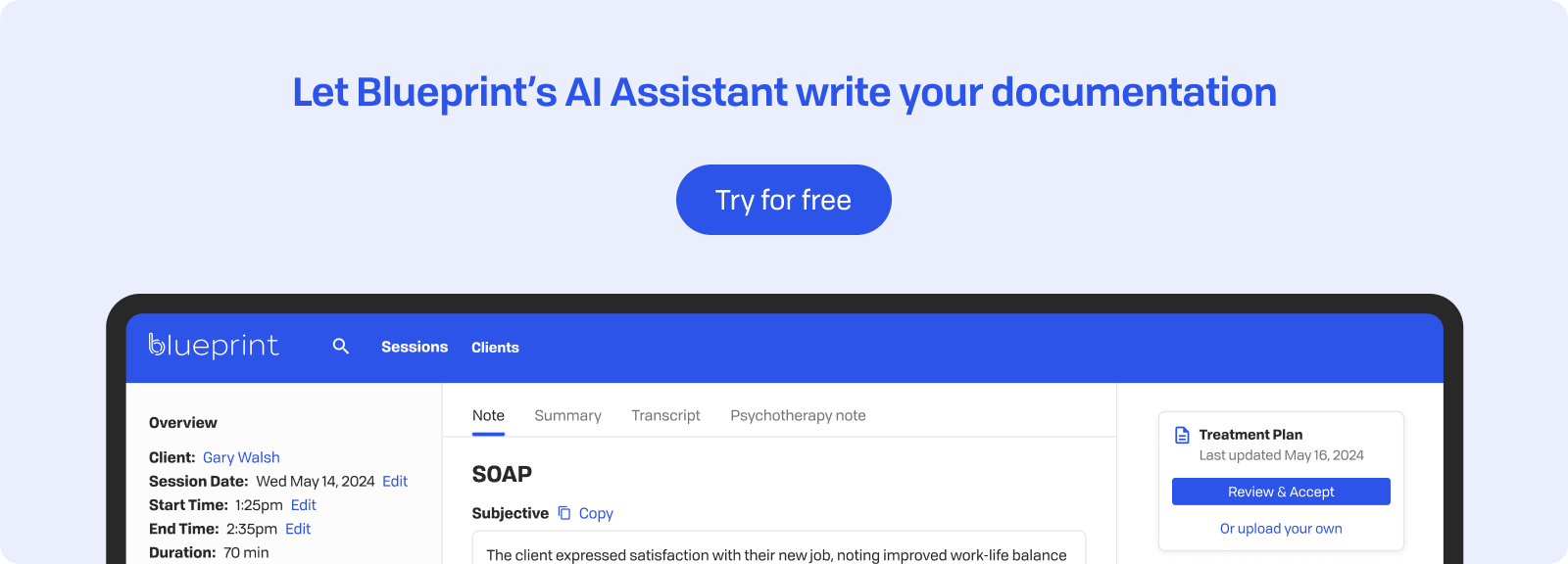

How Blueprint can help streamline your workflow

Blueprint is a HIPAA-compliant AI Assistant built with therapists, for the way therapists work. Trusted by over 50,000 clinicians, Blueprint automates progress notes, drafts smart treatment plans, and surfaces actionable insights before, during, and after every client session. That means saving about 5-10 hours each week — so you have more time to focus on what matters most to you.

Try your first five sessions of Blueprint for free. No credit card required, with a 60-day money-back guarantee.